Why I Want to Die

No, I don’t want to die right now. For all its problems, I genuinely love my life. Even if I live to be a hundred, I will probably want to live a hundred years more. But I do not want to live forever.

Some argue that death is not bad since we didn’t care about not being alive before we were born and we won’t be around to care after we die. This argument has been around for at least a couple thousand years, since Epicurus stated in his Letter to Menoeceus that “Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not. It is nothing, then, either to the living or to the dead, for with the living it is not and the dead exist no longer.”

However, I think Epicurus got it wrong. There are things we value very deeply that death would take away from us, whether it’s the ability to fall in love and get married, to be there when your child takes her first steps, to write that book you’ve always wanted to write, or simply to have one more day with the one you love. Death takes away things of great value, even if we won’t be there to mourn their loss.

We want to go on living because there are things we want to do, whether those goals are long term goals like becoming a nuclear physicist, or short term goals like going to see our son’s play. We have far more things we want to do then we have years to do them. Even if we live for one thousand years, there will still be things left that we want to do.

While I love life, I would not want eternal life, either on earth, or in heaven. I don’t think most people have really thought about what it would mean to live forever. It would mean that you would have time to accomplish every single goal that you’re capable of accomplishing. You could be a conductor, a teacher, and a marine biologist. You could hike every mountain and sing every conceivable song. But you might also lose motivation to accomplish your long term goals. Why put in the hard work to become a brain surgeon if you could always put it off until tomorrow? But regardless of how motivated you are to accomplish your goals, there will come a point at which you will have accomplished every goal you really wanted to accomplish. You will have nothing left that will make life worth living.

Even if we were in a realm where we could do anything, from walking through walls to talking to George Washington, there are only a finite number of possible things a finite mind can experience in one minute. There is only so much sensory data we can take in, and only so many ways that our neurons can fire. Since there are only a finite number of one minute experiences, there would only be a finite number of billion minute experiences too (just like how there are finite digits and also finite billion-digit numbers). We could even do every possible googolplex year experience a googolplex times.

However there are some things we want to do again and again. Just because I achieve my goal of eating a delicious pizza doesn’t mean I would never want to eat an identical pizza in the future. Even if I do everything I could possibly do, I would still want to redo some of it. But eventually, the pleasure would diminish. I don’t think sex with Brad Pitt would be as much fun if you’ve already done it a googolplex times.

At some point, there would be nothing new to accomplish or experience, and all I could do is relive past experiences. It may be fun for a while, but I think eventually I would find it unfulfilling.

But maybe we’re not in a heavenly realm where we can do anything, and there are barriers preventing us from achieving all our goals right away. Let’s say that I was only able to achieve one new goal every billion years. Since there are finite goals, there would still come a point where I achieved all my goals, and then a point where I had achieved all my goals a googolplex times.

One way to avoid the problem of getting tired of things would be if I kept forgetting what I did in the past. I could then do exactly the same series of things over and over again without ever getting bored. However, I don't see why living an identical life over and over again is necessarily more valuable than living that life once. Either way I end up achieving and enjoying exactly the same things. I also think that my memories are such an important part of what makes ‘me’ ‘me’, that if you took them all away, it may no longer be ‘me’ that is living forever.

Another way around the problem would be if my brain was changed so that I behaved differently. Maybe the brains of pigs (or some other animal) are set up so they would enjoy eternal life. If so, my brain could be gradually changed until it was identical to that of a pig. "I" would then enjoy eternal life.

I’ve thought a lot about it, and I can’t think of any type of immortality worth wanting. Not only would eternal life be endlessly repetitive, it would deprive life of its value. It is because life is finite that every moment of my life is precious. I will do some amazing things in my life, but there will be other things that I will never get to do. What I get to do will be based on the choices I make and the work I do. I will not have infinite time to try again, and that makes my life’s successes so much sweeter. My choices matter. Every minute matters. That is why I love life, and why I want to die.

Thursday, July 22, 2010 | 9 Comments

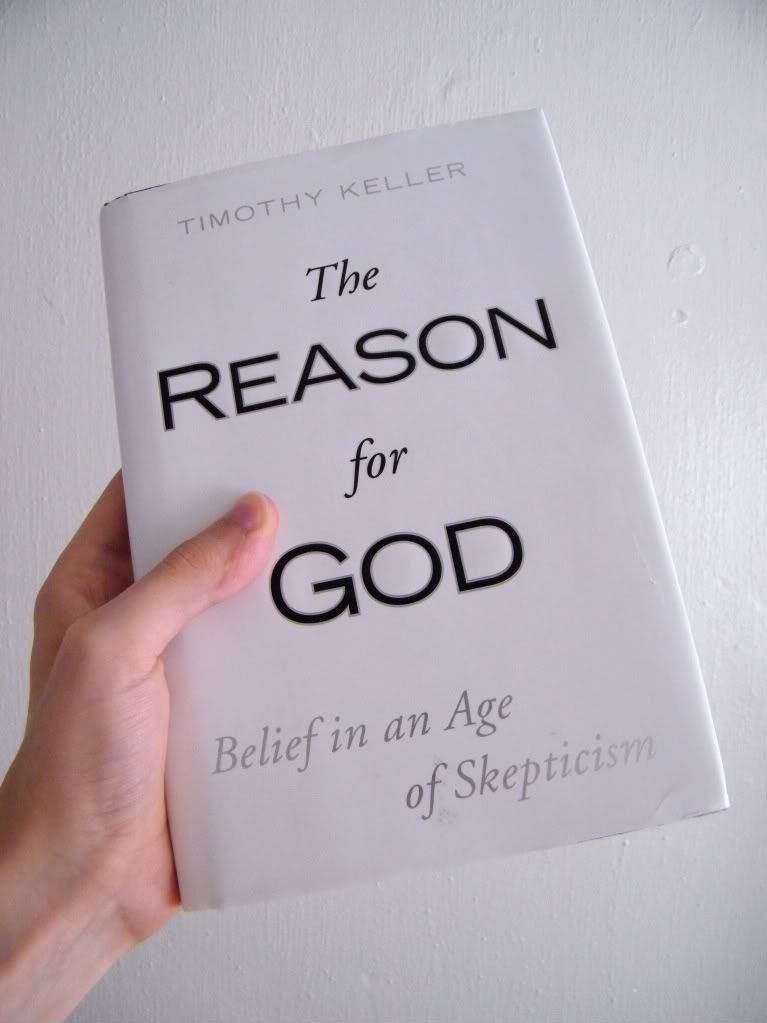

Review of “The Reason for God” (Part 1)

Even though I believe the book fails at persuading thoughtful nonbelievers, it has become quite popular. It has been the top selling apologetics book an Amazon for months and even reached #7 on the New York Times Best Seller list for non-fiction. I’ve also spoken to a couple people who highly recommended Keller’s work.

Although I find the book unpersuasive, Keller does make a lot of good points. He even recognizes that religion is one of the main barriers to world peace. “Each religion informs its followers that they have “the truth,” and this naturally leads them to feel superior to those with differing beliefs. … Therefore, it is easy for one religious group to stereotype and caricature other ones. Once this situation exists it can easily spiral down into the marginalization of others or even to active oppression, abuse, or violence against them” (page 4).

I also completely agree with what he says about doubt. “A person’s faith can collapse almost overnight if she has failed over the years to listen patiently to her own doubts, which should only be discarded after long reflection. Believers should acknowledge and wrestle with doubts—not only their own but their friends’ and neighbors’. It is no longer sufficient to hold beliefs because you inherited them” (xvii).

This should apply not only to believers, but to atheists as well. Atheists should be just as willing to consider objections to their beliefs. As Keller points out, if someone believes that God does not exist because she says that “There can’t just be one true religion,” but does not have good evidence to back up that statement, believing it is an act of faith.

However, Keller errs when he says that “All doubts, however, skeptical and cynical they may seem, are really just a set of alternate beliefs. You cannot doubt Belief A except from a position of faith in Belief B. … Every doubt, therefore, is based on a leap of faith” (xvii). If I say that I’m going to flip a coin and it will come up heads, you can doubt that it will come up heads without having to believe that it will come up tails. If you don’t think that we have a good enough idea of the values in the Drake equation to say whether there is intelligent life on other planets, you can doubt someone’s claim that there is extraterrestrial life without believing that there isn’t. It is possible to simply say, “I don’t know.”

In order to doubt that Christianity is true, you don’t need an argument to show that it is false, just as you can doubt that invisible unicorns exist even without an argument showing that they do not exist. Of course, many atheists do believe that things like the problem of evil are evidence against Christianity, but even if all those objections were refuted, it would not show that Christianity is true. There could still be no good reasons to believe in it, just as there are no good reasons to believe in invisible unicorns (as far as I know).

Early in the book, Keller describes his own religious journey. Growing up in the ‘60’s, he saw “two camps before [him], and there was something radically wrong with both of them. The people most passionate about social justice were moral relativists, while the morally upright didn’t seem to care about the oppression going on all over the world” (xii). He was drawn to the former camp, but kept asking himself: “If morality is relative, why isn’t social justice as well?” I agree with Keller that both of these camps have it wrong, but these are definitely not the only camps. While Keller ended up in the camp of Christians who care about social justice, I ended up in the camp of atheists who reject moral relativism and care about making the world a better place.

The Reason for God is broken up into two parts. In the first half, Keller attempts to refute what he sees as some of the incorrect faith beliefs of nonbelievers which stand in the way of them believing in God. In the second, Keller explains what he sees as sufficient reasons for believing that Christianity is true.

He opens the first half of the book by addressing the claim that “There can’t be just one true religion.” I agree with him that this is a bad reason for thinking that Christianity must be false. The diversity of religions does mean it’s unlikely that we happened to be raised into the one true religion and gives us a good reason to examine whether there is evidence for our religious beliefs. But it does not show that all religious beliefs are false or that all religious beliefs are true any more than a diversity of moral beliefs proves moral nihilism or moral relativism.

In the next chapter, he engages with the biggest objection many non-believers have: the problem of evil. He rightly points out that “just because you can’t see or imagine a good reason why God might allow something to happen doesn’t mean there can’t be one” (23). I agree with Keller that my own inability to think of good reasons why an omnibenevolent God would permit the Holocaust is no proof that there aren’t any.

Even if horrendous evils are not a logical disproof of God, they at least seem like evidence against the existence of such a God. This world is far different than what I would expect if the world had been created by a perfect God. However, a lot has been written on the problem of evil, so I feel I should read more before being confident that the evidential argument from evil can withstand all objections (I’m particularly interested in reading The God Beyond Belief, in which Christian philosopher Nick Trakakis argues that the evidential problem of evil does provide evidence against Christianity).

But even if Keller’s approach, which is known as skeptical theism, is a sufficient answer to the problem of evil, it has consequences that Christians might be unwilling to accept. Skeptical theism asserts that an inability to think of a morally sufficient reason for God having done something is no evidence that God didn’t have a morally sufficient reason. As I discussed in previous post, if skeptical theism is true, then our inability to think of a morally sufficient reason for why God would lie to us about heaven existing is no evidence that God didn’t have a morally sufficient reason to lie about heaven. Accepting skeptical theism means accepting that you have no good reasons to believe that the most basic tenants of the Christian faith are true.

Keller also describes people who went through periods of suffering and became better because of it. This is a good point. I’ve had some rough periods in my own life, and I definitely think that temporary suffering can sometimes help change one’s life for the better. However, it is very hard for me to accept that that the Holocaust made all the Jews better off or that a young girl who is gang raped and then killed benefits from the experience.

Keller then argues that evil is actually a bigger problem for atheism than for theism. He says that without God, there is no good basis for saying that an action is good or evil. But here he is guilty of what he just accused atheists of. He assumes that an inability to think of a good basis for morality outside of God means that there can’t be one. I, as well as many moral philosophers, do believe that morality can exist without God. But even if we are all wrong, this wouldn’t prove that God exists, it would instead show that theism would be more desirable than atheism for people who want morality to exist. Similarly, belief in God is more desirable for people who want to live forever, but this doesn’t prove that God actually exists.

Christianity also has a problem of saying what the basis of morality is. Many Christians say that it is God’s benevolent nature. But is his nature good just because it happens to be God’s, or is it good because it is consistent with some principles of moral goodness. If it’s the former, then if God had thought murder was good and love was evil, murder actually would be good and love would be evil. It would then be omnibenevolent of God to hate and kill everyone. In this case, it seems meaningless to call God good. But if you take the latter approach and say that God’s nature is good because it adheres to principles of moral goodness (such as kindness and fairness), then you still have to give a basis outside of God for those moral principles. And this is even more problematic for Christians, since it is very hard to come up with an ethical system under which all the things the Bible says that God did would be moral (1 Samuel 15, Numbers 31, and Exodus 11 are particularly problematic).

Not only does atheism provide a better answer to why there’s evil in the world (animals that kill and eat other animals have a better chance of surviving and passing on their genes), it is also better able to give a basis for morality.

Thursday, July 15, 2010 | 8 Comments